Watch the ASL Interpretation of this post here.

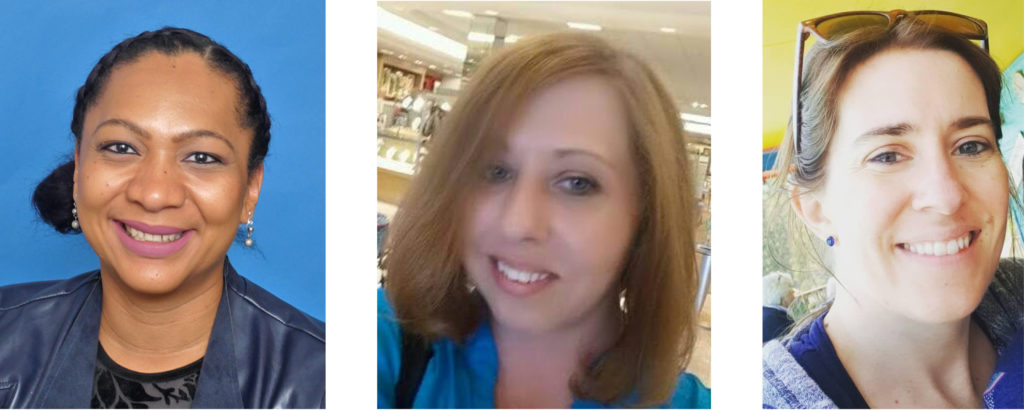

The aftermath of a violent event, like a shooting, can create feelings of trauma and grief. Trauma affects people who were present at the scene of violence, families and loved ones of victims, and entire communities. To better understand how these events impact us, we spoke with three WellPower staff members:

- Stephanie Johnson, LCSW, LAC – Director of Community Relations and Public Policy

- Jade Werner, MSW, LAC – Clinical Case Manager and Grief, Loss & Relapse Prevention Group facilitator

- Ashlie Lund-Richardson, LCSW, LAC – Assistant Program Manager

How do violent events, like a shooting, impact feelings of trauma and grief?

Ashlie: We can experience a sense of grief or loss anytime something changes in the path we envisioned following. This can include things like a change in career, change in family dynamics, and an act of violence. We grieve what we thought was or what we thought should be.

Jade: Anything that impacts a community negatively can create feelings in individuals. These can include shock, sorrow, numbness, anger, disillusionment, trauma and grief. Violent events, like the shooting in Boulder, can shake up our assumptive world (our baseline knowledge of how the world exists).

What are common reactions to experiencing a violent event, both as a victim and as a community member?

Jade: First, we need to understand the difference between direct trauma and vicarious trauma. Direct trauma is something that influences the victim. This could be someone harmed, a person who saw someone harmed, or someone who was present at the scene. Vicarious trauma is seeing or hearing someone else’s trauma. You can learn more about vicarious trauma in this post about coping with a tragedy.

People who are victims of direct trauma will likely experience immediate acute stress. That often looks like: replaying what happened, what they could have done differently, changing eating habits, trouble sleeping, and more. Victims of vicarious trauma may have some of the same symptoms. Often, they experience trouble sleeping, trouble with concentration, and fear for themselves or loved ones.

Where we need to be especially mindful is knowing that this acute stress can warp into Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). We also need to be careful in how we compare and understand grief around violent events, because the grieving process is so deeply personal.

What is re-traumatization and how do incidents of violence, like a shooting, impact it?

Jade: Re-traumatization is a conscious or unconscious reminder of past trauma. It usually results in a re-experiencing of the initial trauma event. A situation, an attitude or expression, or certain environments that replicate the dynamics (loss of power/control/safety) of the original trauma can cause re-traumatization. People and communities can experience trauma and re-traumatization. Here is a study we’ve used to understand re-traumatization.

If someone has experienced violence or shootings in the past, being in a situation like the Boulder shooting can bring back the flood of trauma and grief from the past experience. It can compound previous trauma and increase the risk for PTSD.

Do feelings of trauma and grief only center around people/loved ones? Why or why not?

Stephanie: Trauma and grief do not only center around people/loved ones. They also don’t only center around people directly connected to a violent event. Violent events shake our sense of normalcy, and so it’s common to grieve the loss of what our reality was moments before this event happened. We grieve the loss of safety, control, and trust. Those things may be intangible, but they are very real and the loss of them can have significant impacts on how we experience everyday life. Because they’re less tangible than a person is, it can be common for us to experience guilt over grieving those losses; however, that grief is normal, and honoring or grieving those losses can be a very healthy part of figuring out how we will move forward from these events.

Ashlie: A sense of grief or loss can be experienced anytime our view of our path has changed. Our experience of grief can look differently depending on what type of loss we are experiencing (ie. loss of job, loss of loved one, hearing about acts of violence in our community). It is important to validate our own experience of grief, seek support when appropriate and find movement through our grief/sadness. Again, that movement and process may look very different depending on the type of loss and intensity of emotions surrounding that loss, what our support system looks like and how strong our resiliency or coping ability is in that moment.

How do shootings impact our assumptive world?

Stephanie: Shootings can change things for us in an instant. We go through life expecting to have some sense of what is safe and what may be unsafe. There are certain places or times of day where many people assume things are safer. The middle of the day and/or public places generally feel safe, and we assume that our guard doesn’t need to be up. Shootings disrupt those assumptions, and because of that, we may feel angry or betrayed. As more shootings happen, we often start to add to our internal list of places that aren’t safe. That leads us to question everyday decisions that we’ve always just assumed we could make.

Jade: When a negative life event has challenged our world in a way that our assumptions no longer make sense, it can create these feelings of trauma and grief. Most of us assume that when we go to the grocery store, we’re safe. The shooting in Boulder flips that notion on its head and tells us we could be going through our daily life and not be safe.

How does trauma from sudden violent events interact with trauma from ongoing events, like COVID-19?

Ashlie: Think of someone’s sense of vulnerability. When we are already experiencing increased vulnerability, like managing the impact of our lives from COVID-19 (change in routine, loss of job/financial impact, increased loneliness etc), we can sometimes be even more at risk for being strongly impacted by another significant event (act of violence etc). This can impact our resiliency or ability to tolerate and move through our emotional experience of these significant situations.

Stephanie: Trauma compounds over time. Ongoing events, like COVID-19, create long periods of time where people are living with heightened adrenaline and emotion and often aren’t able to fully return back to a baseline level of those things. When a sudden, violent event happens during an ongoing trauma, we’re already entering that experience without our full tank of emotional capacity. That can result in feeling like we’re less capable of responding to the new trauma and maybe that we can’t even handle recognizing that it happened. It can also result in elevated reactions to common stressors.

When we’re dealing with multiple traumatic experiences, our bodies and minds can start to treat everything like a threat and possible trauma. Maybe we lock our keys in the car and would normally view that as an inconvenience and frustration, but now we feel like it breaks us. Or, our partner pokes fun at us and instead of laughing with them, we yell and get into a big argument. Ongoing traumatic events can really draw out those extremes of either numbing ourselves to the experience of new traumas or feeling those new things so much more strongly than if we weren’t already emotionally exhausted.